Last weekend, I sat in a fiction workshop with Randall Kenan and 9 other very sharp writers. Some of us came to this workshop, sponsored by The Raleigh Review, through poetry. We acknowledged spending the majority of our time crafting poems but admitted we also had a leaning toward telling stories. At least one person didn’t think he was a storyteller at all. Trust me, he was kidding himself. His in-class exercises were just amazing.

I first encountered the work of Randall Kenan when I sat on the board of Carolina Wren Press, the nonprofit small press that published some of his early works. His characters made me very proud to be Southern, and I felt as a reader I had found someone who could adequately describe the world — its nuances, sounds, smells — that was my native soil.

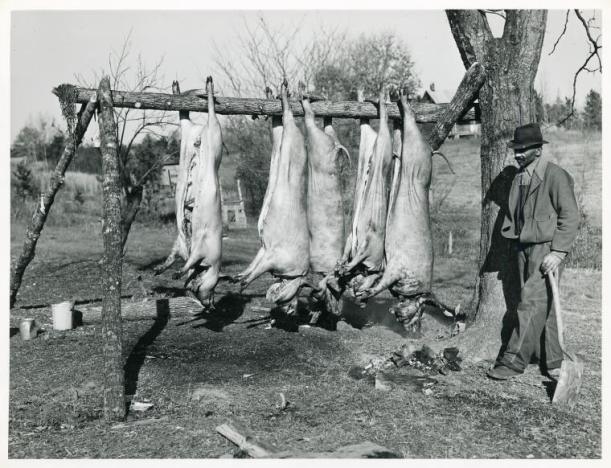

As I said to Kenan in workshop, one of the most memorable passages from his work involved a hog killing. I think I grit my teeth and grimaced through the reading of the entire passage. Here’s some of it:

“Surely someone told you of the huge vat of water over the fire, the blue-red flames licking the sides. Her they will dunk the fat corpses, to scald the skin and hair. Four men, two on either end of two chains, will roll, heave-ho, the thing over into the vat and then round and round and round in the boiling water, until you can reach down and yank out hair by the handfuls. They will roll the creature and scrape it clean of hair and skin, and it will be pinkish white like the bellies of dead fish. They will bind and skewer its hind feet with a thick wooden peg, drag it over by the old smokehouse, and then hoist it up onto a pole braced high, higher than a man.

Then someone will take a great silver knife and make a thin true line down the belly of the beast, from the rectum to the top of its throat. He will make a deep incision at the top and with a wet and ripping sound like the bursting of a watermelon, the creature will be split clear in two, its delicate organs spilling down like vomit, the fine, shiny sacs waiting there to be cut loose, one by one. The blood left in the hog will drip from the snout, in slow, long drips, dripping, staining the brown winter grass a deep maroon. But I’m certain you’ve witnessed all this, of course … ” From A Visitation of Spirits, Grove Press, 1989

When I was a little girl, I was not allow to attend hog killings. My father kept me safely tucked away in my grandmother’s kitchen so that I didn’t have to see the gore. Instead of being outside in the thick of the action, I was rolling dough for biscuits or helping Grandma Doe stir a pot on the wood-burning stove. As I’ve come to know my father, I recognize this sequestering habit as more an act of chauvinism than protection. My brother, two years younger, was always allowed to attend these kind of festivities. I told Randall Kenan that his book and its vivid images gave me my front-row seat to a hog killing. Before I read it years ago, I had no idea how it happened.

Over time, I have become quite cynical of workshops. Unless they are generative workshops that will allow me to walk out with new drafts in hand, I usually tend to avoid them. My goal with this workshop, though, was to force myself to think about how to enter a story I have wanted to tell for a long time. One of the other writers in workshop with me mentioned something about sometimes preserving some of the stories that you have and not publishing them until all the people they reflect are dead. Her comment made me know that for years, this is what I’ve been engaging in myself, a subconscious refusal to address the real issues of this story by writing almost anything else. The people the story will reflect are not dead. But I feel it is time for me to explore this. Even if it never gets published, it will be written and out of my head.

The exercise we got in workshop was to explore character by doing a series of “He _______” statements like those in the opening of Ron Hansen’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. It starts like this:

“He was growing into middle age and was living then in a bungalow on Woodland Avenue. Green weeds split the porch steps, a wasp nest clung to an attic gable, a rope swing looped down from a dying elm tree and the ground below it was scuffed soft as flour … Whenever he walked about the house, he carried several newspapers … with a foot-long .44 caliber pistol tucked into a fold … He played by flipping peanuts to squirrels. He braided yellow dandelions into his wife’s yellow hair. He practiced out-of-the-body travel, precognition, sorcery. He sucked raw egg yolks out of their shells and ate grass, when sick, like a dog. He would flop open the limp Holy Bible that had belonged to his father, the late Reverend Robert S. James, and would contemplate whichever verses he chanced upon, getting privileged messages from each.”

This style goes on for pages and, ordinarily, would make me tired. But this passage gives a very thorough character sketch. As a literary device, it gives the reader an abundance of information about the character. Our take-home assignment for Day 1 was to imitate it. Because I am prone to be quirky, I sustained the exercise for about 20 minutes, and then it went off on its own tangent to become the story. By the time I was done, my story was being told from the point-of-view of a house that had been in existence for several generations. At some point, I guess the muse decided that walls literally could talk — and then made them talk. We’ll see where it goes, but I’m looking forward to building this story.